By Louise Carrie Wales, PhD., Upper School Art Teacher

When speaking with GCDS families, I often pose a simple question: when did you come to believe you lacked any artistic talent? In other words, when did you lose your confidence — whether in the studio, on stage, or with an instrument? Many of us have a story to tell that underpins our pervasive arts-related insecurity. And, yet, human beings are defined by our ability to think creatively as evidenced in millennia of astounding artistic production. Philosopher Henri Bergson coined the term “Homo Faber” and asserted that our inherent ‘will to make’ separates us from other species. It is, by all definitions, in our DNA. How then do so many of us abandon our natural inclinations? Sir Ken Robinson explains, “I believe profoundly that we don’t grow into creativity; we grow out of it. Often, we are educated out of it.” As I see it, this outcome is devastating. For educators, particularly in the arts, it is our paramount responsibility to nurture and encourage creative endeavors — at every stage of learning — respecting the tremendous fragility of our innate artistic spark.

At GCDS, we are fortunate to have a full roster of talented and qualified faculty in the arts across all disciplines N–12. We also benefit from administrative support for and commitment to our diverse efforts. This bit of writing should simply serve as a reminder and defense of the Arts’ fundamental importance in the lives of our students — today and well into their futures. In a paragraph detailing what skills current workforces require, the Wall Street Journal repeatedly lists “Creative thinking and resilience, flexibility and agility … along with curiosity and lifelong learning.” Problem solving also tops the list year over year. The arts foster all of these skills in spades.

Simply put, a robust art education, encompassing visual, performing, and musical arts, is critical for cultivating creativity, cognitive development, emotional intelligence, and skills applicable to the real world. In Arts with the Brain in Mind, Eric Jensen asserts that “the systems they nourish, which include our sensory, attentional, cognitive, emotional, and motor capacities, are, in fact, the driving forces behind all other learning.” The research is clear. There are countless studies from well-reputed academics (Johns Hopkins University among many others) that draw clear connections between musical training as enhancing spatial-temporal skills and math comprehension. Moreover, musical training strengthens auditory processing, discipline, and teamwork. Playing in a band requires both commitment and collaboration. Similarly, performing on stage boosts memory retention and social understanding. Consider any GCDS production (most recently the Middle School’s Alice in Wonderland and the Upper School’s April rendition of School of Rock) and you will witness every kind of child finding their voice and delivering lines with power and effect in front of large audiences. It’s a remarkable opportunity that boosts public speaking and self-confidence. These collaborations create life-long memories while promoting empathy through character development.

The visual arts, in turn, enhance fine motor skills, spatial reasoning, and problem solving. As early as Nursery, children negotiate their worlds visually through drawing, diagramming, painting, and sculpting in clay. Recent research supports the notion that hand work — from notetaking to drawing to painting — creates neural pathways in the brain that are bypassed when working digitally. Frank Wilson dedicates his book, The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture, to this particular investigation concluding that the brain develops more rapidly when humans are engaged in creative problem solving — such as early making of tools and, now, drawing in the analog world as opposed to digitally. As students observe and learn to truly see their surroundings, the resulting artworks can be astounding.

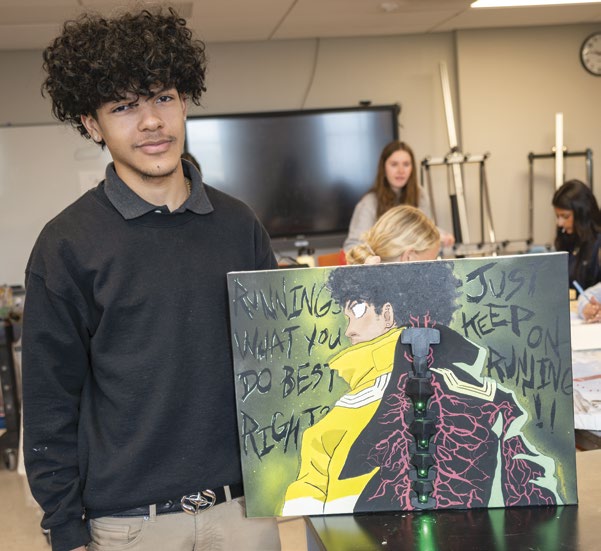

We have countless examples among our Upper School artists, but three stand out as evidence of art’s ability to forge powerful connections between subject matter and the real world. In response to a project entitled ‘What Inspires You?’ Ninth graders Bea Renwick (above) and Romell Sarsoza (right) are creating paintings that require coordination of disparate skills — from makerspace circuitry to mapping to painting and collage. Each one had to reflect deeply about the life they are leading and what experiences have impacted them. Bea’s painting, a circular canvas mixed-media work, illustrates her impressive array of travels around the globe using collage, painting and mapping pins. Romell, in turn, has 3-D printed a spine and included green lights to enhance an anime inspired self-portrait. The two answers could not be more different, but reflect the students’ identities and life experiences in creative and compelling ways.

We have countless examples among our Upper School artists, but three stand out as evidence of art’s ability to forge powerful connections between subject matter and the real world. In response to a project entitled ‘What Inspires You?’ Ninth graders Bea Renwick (above) and Romell Sarsoza (right) are creating paintings that require coordination of disparate skills — from makerspace circuitry to mapping to painting and collage. Each one had to reflect deeply about the life they are leading and what experiences have impacted them. Bea’s painting, a circular canvas mixed-media work, illustrates her impressive array of travels around the globe using collage, painting and mapping pins. Romell, in turn, has 3-D printed a spine and included green lights to enhance an anime inspired self-portrait. The two answers could not be more different, but reflect the students’ identities and life experiences in creative and compelling ways.

.jpg) The third powerful example was created by Lilly Patchen (left), also a 9th grader, during the Art to Heart Intersession course and is evidence of art’s impact on community and the development of emotional intelligence. Students considered five immigrant stories through in-person interviews. They subsequently responded to the story that resonated most for them personally. When describing her work, Lilly wrote “along the way, Lala and her family had to throw themselves with their suitcases onto mountains from a moving train. I wanted to incorporate this alarming scene in my artwork, so I sculpted mountains and a train on the ‘immigration’ bookend to symbolize the hardships and difficulties of immigrating.”

The third powerful example was created by Lilly Patchen (left), also a 9th grader, during the Art to Heart Intersession course and is evidence of art’s impact on community and the development of emotional intelligence. Students considered five immigrant stories through in-person interviews. They subsequently responded to the story that resonated most for them personally. When describing her work, Lilly wrote “along the way, Lala and her family had to throw themselves with their suitcases onto mountains from a moving train. I wanted to incorporate this alarming scene in my artwork, so I sculpted mountains and a train on the ‘immigration’ bookend to symbolize the hardships and difficulties of immigrating.”

What Lilly created in a short span of time is astounding in its symbolism, iconography and skill. She listened to the story, responded with her creative work and then, will give the finished work to the person who inspired her — a full circle moment meaningful to all concerned. Lilly’s experience reminds me of Elliot Eisner, Professor Emeritus of Child Education at Stanford, who said “with the arts, children learn to see. We want our children to have basic skills. But they also will need sophisticated cognition, and they can learn that through the visual arts.” What Bea, Romell and Lilly’s artworks have in common is a profound ability to ‘see’ well beyond the surface — and resulting interpretation of their surrounding worlds.

In a changing landscape of increasing digitization and AI, let this brief meditation on some key factors in support of a robust art education linger in our minds. It seems fitting to end with John F. Kennedy’s words: “To further the appreciation of culture among all the people. To increase respect for the creative individual, to widen participation by all the processes and fulfillments of Art — this is one of the fascinating challenges of these days.” His words resonate now more than ever.

.JPG&command_2=resize&height_2=85)